The Beach Boys had the answer to this... It takes "Good, Good, Good... Good Vibrations"

Posts made by Dr GO

-

RE: Is Air Needed To Play The Trumpetposted in Embouchure and Air

-

RE: How To Play Trumpet With Less Tensionposted in Embouchure and Air

I have always found a good Gin and Tonic lowers trumpet playing tension for me... Yep, that's the solution

-

RE: Intro from a Global Moderatorposted in Announcements

@fels said in Intro from a Global Moderator:

@Dr-Mark

Training dogs and practicing the trumpet are similar endeavors. Once started, both require constant attention to detail and commitment of time. It is never "over."Not to mention... Ruff!

-

RE: Best Off-brand Trumpetsposted in Bb & C Trumpets

@barliman2001 said in Best Off-brand Trumpets:

@Dr-GO Here in Vienna, I am always eager to welcome any former TMers or TBers - as Sethoflagos, rowuk and SSmith1226 can witness.

Great. Be assured, I will look you up the next time I am in Vienna. Last time I was came through Vienna was in 1972 after playing the Graz Music Festival. Did not get to experience much of Vienna... Had some bad wine... ruined my trip through Vienna.

The next time will be quality, especially with having the chance to share experiences with you in person. ALSO would LOVE the opportunity to coordinate a visit that would allow me to hear your wife sing at the opera.

-

RE: Christophe LeLoilposted in Jazz / Commercial

I purchased his amazing album Line 4. Very creative way he used to compile a collection of mostly original tunes by his quartet. I am providing a sample from this album as well. Christophe is one of to most uniquely original jazz trumpet performers I have had the chance to experience. He has a sound and technique that instantly identifies him as the artist.

ENJOY:

-

Christophe LeLoilposted in Jazz / Commercial

Let me introduce the TB community to Christophe LeLoil. He was a TM member and very interactive on that site. He is and amazingly talented French jazz trumpet player that has a new album out. Just want to make sure all hear at TB is provided the opportunity to hear his work and follow a sample to his new link:

http://music.apple.com/fr/album/les-quatre-vents/1480562105

Here is the Christophe's actual text announcing his project: So glad to announce the release of 'Les quatre vents' a quartet setup of original compositions. This was recorded last winter at famous la Buissonne studio, which is currently used for most of the ECM productions...just to say about its sound. Published by LaborieJAzz Label, and available on every platforms.

-

RE: Intro from a Global Moderatorposted in Announcements

@Dr-Mark said in Intro from a Global Moderator:

@Niner said in Intro from a Global Moderator:

Give me a second to figure it out.

Why try? The darned thing isn't even transposed to Bb.

Hey, its in

This is very close to G# which can be played on any keyed instrument -

RE: Best Off-brand Trumpetsposted in Bb & C Trumpets

@SSmith1226 said in Best Off-brand Trumpets:

@Dr-GO

Don’t you mean Schlub? Schagerl is in Mank, Austria, and I believe George Schlub moved back to Ohio from Singapore.Ooops... yes I do. I will do the appropriate edits. Thanks Dr. Smith!

-

RE: Olds Trumpet retail list from 1967posted in Historical & Collector's Items

@Niner said in Olds Trumpet retail list from 1967:

The top of the trumpet line was the Custom that listed for $675. The top cornet was the Mendez for $525. However, using an inflation calculator $675 in 1967 is equivalent to approximately, depending on which online calculator you use....$5188.99 in 2019. The Mendez cornet is now the equivalent of $4035.88.

This was the year my parents bought me the Olds Recording

They got a better deal for this through Buddy Rogers Music (in North College Hill section of Cincinnati) as I believe they told me they paid $375 for the horn that year.

-

RE: How about a "Random Meaningless Image...let's see them string"?posted in Lounge

@SSmith1226 said in How about a "Random Meaningless Image...let's see them string"?:

Los Angeles

Not to mention their garages as well!

-

RE: Best Off-brand Trumpetsposted in Bb & C Trumpets

@Kehaulani said in Best Off-brand Trumpets:

@Dr-Mark said in Best Off-brand Trumpets:

(made by Schagerl ) the best.Maybe she should've tried it with mustard and relish.

Should any of you relish the opportunity to come visit and purchase a Schlub horn in person, please drop me a line, as the manufacture has moved into the Dayton area. Always looking for an opportunity to meet more TB members.

-

RE: Intro from a Global Moderatorposted in Announcements

@Kehaulani said in Intro from a Global Moderator:

@Dr-GO What I still want to know, scientifically, is . . . How does Scotty beam someone up?

You asked for it, and here is your answer: (I do not take credit for this and the entire description can be found in the reference https://www.wired.com/1995/11/krauss/ from which the summary below was taken)

If a person were beamed aboard the Enterprise and remained intact and observably unchanged, it would provide dramatic evidence that a human being is no more than the sum of his or her parts, and the demonstration would directly confront a wealth of spiritual beliefs.

For obvious reasons, this issue is studiously avoided in Star Trek. However, in spite of the purely physical nature of the dematerialization and transport process, the notion that some nebulous "life force" exists beyond the confines of the body is a constant theme in the series. The entire premise of the second and third Star Trek movies, The Wrath of Khan and The Search for Spock, is that Spock, at least, has a "katra" - a living spirit - which can exist apart from the body. More recently, in the Voyager series episode "Cathexis," the "neural energy" - akin to a life force - of Chakotay is removed and wanders around the ship from person to person in an effort to get back "home."

You cannot have it both ways. Either the "soul," the "katra," the "life force," or whatever you want to call it is part of the body and we are no more than our material being, or it isn't. In an effort not to offend religious sensibilities, even a Vulcan's, I will remain neutral in this debate. Nevertheless, I thought it worth pointing out before we forge ahead that even the basic premise of the transporter - that the atoms and the bits are all there is - should not be taken lightly.

The problem with bits

Many of the problems I will soon discuss could be avoided if one were to give up the requirement of transporting the atoms along with the information. After all, anyone with access to the Internet knows how easy it is to transport a data stream containing, say, the detailed plans for a new car, along with photographs. Moving the actual car around, however, is nowhere near as easy. Nevertheless, two rather formidable problems arise even in transporting the bits. The first is a familiar quandary, faced, for example, by the last people to see Jimmy Hoffa alive: how are we to dispose of the body? If just the information is to be transported, then the atoms at the point of origin must be dispensed with and a new set collected at the reception point. This problem is quite severe. If you want to zap 1028 atoms, you have quite a challenge on your hands. Say, for example, that you simply want to turn all this material into pure energy. How much energy would result? Well, Einstein's formula E = mc2 tells us. If one suddenly transformed 50 kilograms (a light adult) of material into energy, one would release the energy equivalent of somewhere in excess of a thousand 1-megaton hydrogen bombs. It is hard to imagine how to do this in an environmentally friendly fashion.

There is, of course, another problem with this procedure. If it is possible, then replicating people would be trivial. Indeed, it would be much easier than transporting them, since the destruction of the original subject would then not be necessary. Replication of inanimate objects in this manner is something one can live with, and indeed the crew members aboard starships do seem to live with this. However, replicating living human beings would certainly be cause for trouble (à la Riker in "Second Chances"). Indeed, if recombinant DNA research today has raised a host of ethical issues, the mind boggles at those that would be raised if complete individuals, including memory and personality, could be replicated at will. People would be like computer programs, or drafts of a book kept on disk. If one of them gets damaged or has a bug, you could simply call up a backup version.

-

RE: Intro from a Global Moderatorposted in Announcements

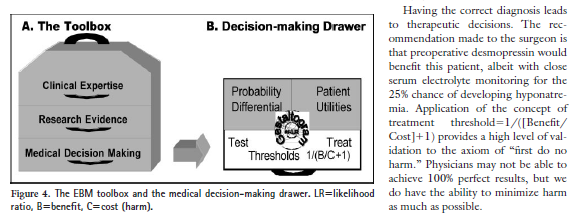

And here is a statistical application I taught at our medical school (This example I published in the American Academy of Pediatrics Publication: Pediatrics in Review,) that instructs physicians how to provide the BEST CHANCE of making the right choice of medication to maximize benefit and minimize harm:

So from theory to the applied practice of medicine, statistics is essential I would argue.

-

RE: Intro from a Global Moderatorposted in Announcements

@Dr-Mark said in Intro from a Global Moderator:

When doing a thesis or dissertation, statistics are often involved and as you know, a statistical test is used on a sample. With that said, when doing research, always try to get a population of something.

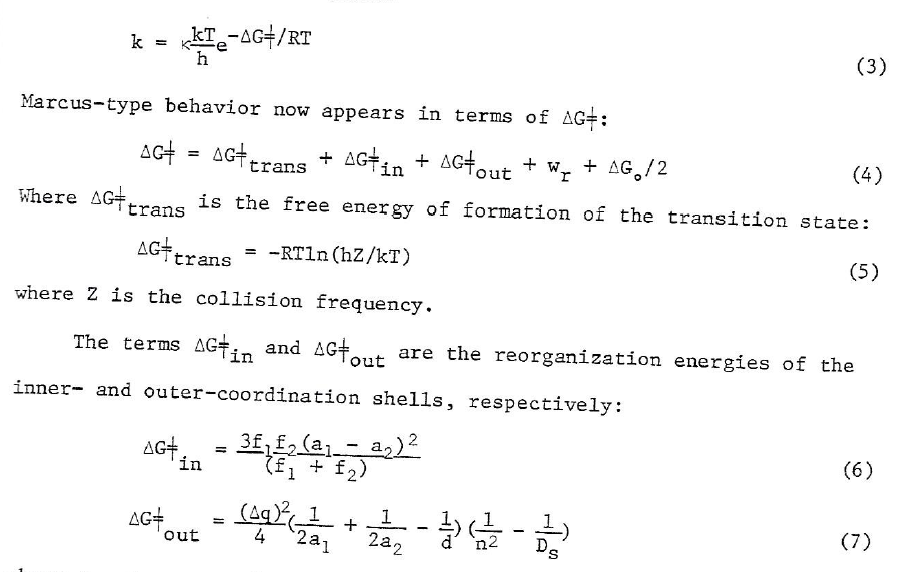

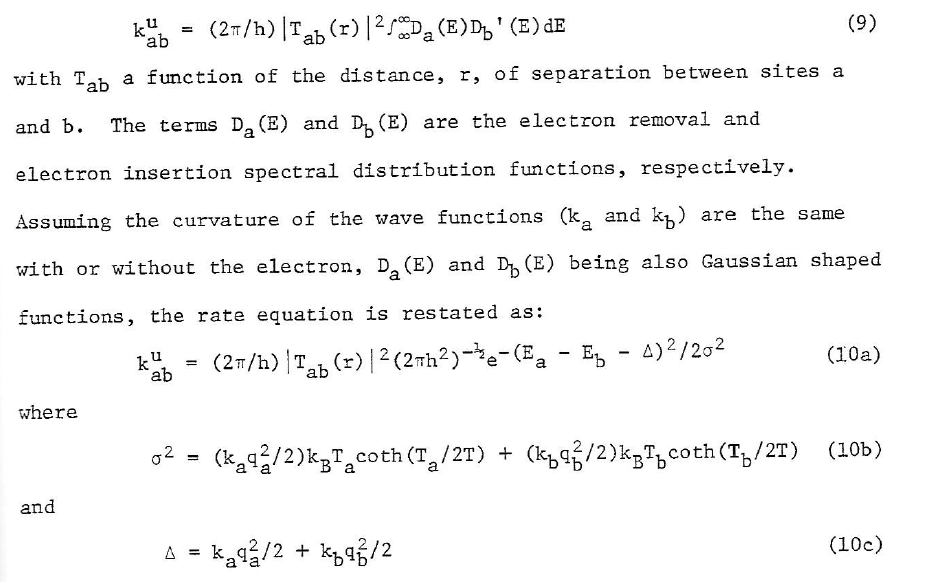

And to illustrate your point, these are the statistical equations I used in my PhD thesis to prove how electrons are transferred down the cytochrome chain of enzymes in our mitochondria, to capture the energy from oxygen into biochemical utilized energy for metabolism:

If electrons travel through the outer hydration sphere of the enzyme on the hydrating water surface, the probability of the transfer rate would equal:

If electron tunneled directly through the atoms within the cytochrome the probability of the transfer rate would equal:

So there you have it: The two possible ways we, as humans, that the oxygen we inhale gets converted to energy... the very same energy we need to play the trumpet... QED.

-

RE: Best Off-brand Trumpetsposted in Bb & C Trumpets

@Curlydoc said in Best Off-brand Trumpets:

@Dr-GO what is the mouthpiece on your pocket trumpet?

It's a 1946 Martin 10. Very flat cup, very long shaft. It somehow makes that Pocket Trumpet sing!

-

RE: Intro from a Global Moderatorposted in Announcements

@Dr-Mark said in Intro from a Global Moderator:

Academically, I'm a former professor of psychology with an additional academic background in Business and Industrial Relations and my specialty was to teach undergraduate and graduate level statistics and research methodology and undergraduate and graduate level economics..

What a coinquedink. I too was a professor of medicine and psychology (only medical school faculty member with an appointment at the School of Professional Psychology - teaching somatization and personality disorders) AND taught the statistics course at the medical school! This is why WE understand each other... AND what's the odds of that?

-

RE: Trumpet Playing Peevesposted in Lounge

Why do the women in the flute section have to were form fitting, fluffy sweaters? It's less a playing than a pet peeve.

-

RE: Lead found in brass horn mouthpiecesposted in Lounge

@Niner said in Lead found in brass horn mouthpieces:

If we were to worry about everything that may or may not do us some harm we would never get out of bed in the morning. Of course there is danger in never getting out of bed too I suppose.... besides bed sores.

Ah, Niner, do you know what unnatural synthetics your bed mattress is stuffed with?... AND if stuffed with animal feathers, do you really know what that animal died from?