Company Timelines (Besson, Diston-Keefer, Frank Holton, Vincent Bach)

-

OK, here's one of those content threads we have been talking about. Here are 4 company timelines. Expand, correct, add more companies. Let's add some core content.

Besson

1838: AG Besson builds his first Perinet valve cornet in France1858: AG Besson loses a lawsuit and relocates to England. His wife restarts the firm, continuing the same serial numbers

1867: (or before) The French firm introduces a new concept of a pitch change slide at the last bend of the lead pipe

1880: (or possibly very shortly before) The French firm introduces the first modern wrap valve trumpet, pretty much what people call a Brevete model (though that is not a model name)

1890: The French firm changes names to Fontaine-Besson as a result of a marriage in the family

1894: The English firm is sold out of the Besson family

1914: Austrian deserter Vincent Bach lands a job as assistant principle trumpet in Boston using a Besson cornet. He is promptly provided Gustav Heim’s spare 1914 LP New Holton Trumpet demonstrator.

1930: Elden Benge begins building modified Bessons and then his own horns in the same style, he continues evolving this school of design with the help of Schilke, Autrey and Busch through the end of his life.

1931: Francois Millereau, a former Besson employee, sells his trumpet making business to Henri Selmer.

1932: Fontaine-Besson is acquired by Strasser Margaux & Lemaire

1948: Besson (the English firm) is acquired by Boosey & Hawkes

1957: An insolvent SML sells Fontaine-Besson to Couesnon

1969: An arson fire reduces the Couesnon plant to a pile of broken block and twisted steel. All Besson records and tooling there are lost. (This is the end of direct production of F.Besson horns)

1980: Donald Benge teams with Zig Kanstul and Byron Autrey to develop Benge style (French Besson style) trumpets for stencil under the Burbank name and also after 1981, the Kanstul name.

1981: Buffet is acquired by Boosey & Hawkes

1986: Boosey & Hawkes is acquired by Carl Fischer

2001: Carl Fischer’s extensive conglomerate of instrument makers shut down names including B&H. Besson continues.

2003: The Music Group, a venture capital entity, restructures the Carl Fischer companies. Besson designs and tooling were deliberately destroyed and the name moved to a new line of instruments built in India and other locations.

2006: The Music Group becomes insolvent. The Meinl family and Triumph Adler, which already owned B^S and other post-collective East block firms, acquires most of the brands including Buffet and Besson. The resultant Buffet-Crampon company controlled those plus Courtois and York. Besson production returned to Europe at Markneukirchen shortly thereafter.

2019: The tooling and records of the Kanstul company convey the Benge/F.Besson Legacy to BAC Musical Instruments. Autrey’s personal Benge and Kanstul horns, design notes, tools, etc. also transfer from his estate to BAC.

2020: BAC acquires the Benge trademark and begins building the culmination of the work of Besson, Benge, Schilke, Autrey and Kanstul with regard to classic Besson design. Modern Besson designs by Buffet continue, but with no design linkage to any prior Besson instruments

Distin-Keefer

1849: Henry Distin started making instruments in England while still part of his family ensemble that toured performing on Saxhorns.

1868: Distin workshop sold to music publisher Boosey & Co. which continued the serial numbers at the same address.

1876: After a couple years of blowing all his money on failed concert promotions and making a living playing and tending bar, Distin moved to the US to superintend at the "monster" Martin Pollman & Co. works in NYC. (This allowed partner JH Martin 2 years to go work at CG Conn and learn about modern instruments)

1878: Distin started making the same designs he had made in England in partnership with FW Busch in New York.

1880: Distin partnered with former Martin & Co. joint venture partner Moses Slater in New York.

1882: Distin moved to Pennsylvania and started Distin & Pincus, a publisher. Slater continued building the same horns under his own name without Distin.

1884: Henry Distin Manufacturing established in Philadelphia to make horns for JW Pepper.

1889: Distin Manufacturing moved to Williamsport

1890: Distin Manufacturing sold to shop superintendent, Brua C. Keefer.

1909: Name changed to Brua C. Keefer Company.

1960: A grass fire alongside the plant spread to the building. The company never reopened.Frank Holton & Co.

1885: Sousa Band trombonist Frank Holton partnered with JW York, a former apprentice to Louis Hartman and Henry Esbach in the Keat/Graves/Wright tradition at Boston.

1887: York and Holton ceases operations, though was not closed out for many years.

1896: Holton starts a mail-order business selling his “Electric Oil” slide oil for trombones. It does not make money in its first 3 years

1898: Holton opens a small Chicago walk-up store selling instrumental supplies and used band instruments. A few cornets were assembled at the repair bench from a mix of purchased and fabricated parts.

1904: Holton relocated to an entire floor of 107 W. Madison in Chicago for more manufacturing space.

1906: The first half of the Holton factory on Gladys street was constructed. Virtuoso Earnst Couturier joins the firm as a promoter, road man, and possibly designer.

1911: The second half and adjacent shipping/receiving building opened. The New Holton Trumpet debuts as the first serious American orchestral trumpet.

1913: Couturier leaves Holton for a brief partnership with JW York to build the Wizard cornet.

1914: Gustav Heim handed his new assistant at Boston a 1914 New Holton Trumpet demonstrator, as the Austrian deserter had no trumpet of his own. This encouraged Vincent Bach to become a Holton artist.

1916: Couturier buys the William Seidel Band Instrument Company, renames it for himself, and starts building a line of pure conical bore instruments – even trombones. He moves it To LaPorte in 1918

1918: Over a weekend in October, all tooling was relocated to a new facility in Elkhorn Wisconsin, provided free of charge when the firm met a local payroll target – actually ahead of the deadline

1918-19: Holton built a neighborhood of houses to recruit key employees. His home anchored the end of the street, the other end of which ended at the door of the municipal building downtown.

1921: The Holton Revelation Trumpet, in production since December of 1919, was announced formally.

1923: Couturier loses his eyesight, and shortly thereafter his company to Lyon & Healy.

1924: 14 year old “child prodigy” Renold Schilke begins performing with the Holton-Elkhorn band, and apprenticing in brassmaking and gunsmithing at the factory.

1927: Schilke, his teacher Edward Llewellyn, and the Holton design team develop the Llewellyn model variant of the Holton Revelation. Elements of this design would influence the Martin Committee.

1928: Holton buys the defunct former Couturier shop for Lyon & Healy and establishes the Collegiate brand.

1929: The same team develops the first light-weight, very large bore, minimally braced, reversed construction trumpet with Kansas trumpeter and professor, Don Berry.

1932: After an unsuccessful rebranding as “Ideal”, Holton closes the LaPorte facility and moves production of Collegiate instruments to the Elkhorn plant.

1938: Frank Holton sells the company to long time employee Frank Kull.

1944: Frank Kull dies and is succeeded by his son Grover.

1957: Holton begins buying parts and complete built-to-spec horns from Courtois. French valves become commonplace on Holton horns – though not all models.

1965: Leblanc completes a 3-year acquisition of Holton – and promptly goes through 2 new model numbering schemes.

1971: Holton, as part of a wide range of artist-linked models, begins a line of 10 trumpets designed at an intermediate level for young fans of Maynard Fergusson. They become best-sellers.

1981: The Martin design team, by then another arm of Leblanc and charged with all R&D, copies an Elkhart Bach 37, selected at a local store, creating the specifications for the Holton T-101s

2004: Steinway Musical Instruments’ Conn-Selmer division acquires Leblanc

2007: Conn-Selmer halts production at Elkhorn, moving Holton French horns to Eastlake Ohio and merging the Holton brand with King and others on Eastlake low brass.Vincent Bach Corporation

1914: While touring in Britain, cornet artist and Austrian Navy veteran Vincent Schrottenbach learns of the onset of World War One. A soldier behind enemy lines, he quickly books passage on a ship to the US under the name Vincent Bach to elude capture. There he performs with the Boston Symphony for a season, tours the West Coast in 1915, and settles in playing with the Met. He is drafted and becomes a bugle instructor for the US Army in 1918.

1918: Bach sets up a small mouthpiece making shop in the back of the New York Selmer store – probably the smartest move George Bundy made on behalf of his then employer.

1922: Bach incorporates.

1924: Bach begins experimenting in trumpet making, drawing on both the commonplace Besson of the time, and his Holtons.

1925: Bach makes his 45th horn for his new wife’s father, bandmaster Adam Staab (it was his second marriage)

1928: Bach moves out of a small storefront shop and into an actual factory building in the Bronx around serial number 1000.

1953: With an additional 10,000 serial numbers consumed, Bach relocates to a factory in Mt. Vernon New York.

1962: Bach sells the company to his one-time patron, the Selmer company, despite higher offers, and designs both a revised Stradivarius trumpet (the 180) and a new Bundy trumpet for them.

1963: In November, construction of 180s begins at Mt. Vernon while the former Buescher plant on Main Street in Elkhart is readied to relocate Bach to, as the rent charged by the Bach family on Mt. Vernon was considerable.

1965: Selmer moves Bach operations to Main Street in Elkhart.

1974: Selmer moves Bach operations, over time, to the facility on Industrial Drive in Elkhart. Two-piece casings and steel rim wires in 180s phase out over the next few years ending the “Early Elkhart” period.

2004: Steinway Musical Properties acquires Selmer, and with it Bach.

2010: The Bach “Artisan” 190 series trumpets are introduced, featuring a French bead and Early-Elkhart elements such as two piece casings. The non-Artisan “regular” 190s additionally feature steel rim wires. -

Thanks for this.

It is my understanding that Bach have always had 2 piece casings (in spite of some company literature). The change that was made, which is often misunderstood, is that they changed from both halves being yellow brass to the top half being nickel silver and the bottom half yellow brass.

-

Fascinating. Could you tell me why the pre-WWII French Bessons were legendary, how Benge and Schilke came into this mix, and what modern trumpet would be the closest to the Besson? Thanks.

-

“1894: The English firm is sold out of the Besson family”

I would add that the English firm’s name was changed to Besson & Co. at that time.

-

Here’s an obscure one, interesting to me because I own one of his instruments.

H. Lenhert, Philadelphia, was in business from 1867-1914. Henry G. Lehnert (1838-1916), founder of the company, arrived in Boston from Saxony ca 1860 with his brother Carl. Early Boston directories indicate that they both worked either for E. G. Wright or for Graves & Co., then joining Freemantle & Co. before establishing business as Henry Lehnert & Co. In 1866 Henry moved to Philadelphia and started his brass musical instrument manufacturing business. He held a patent for the tapered cornet leadpipe and frequently used Allen rotary valves and German silver in the manufacture of his instruments, which had a very good reputation for quality. In 1875, he patented a line of bell-forward “Centennial” lower brass instruments that rested on the player’s shoulder. From 1876 through 1914, his instruments bore the trade name "American Standard". He and his business passed away in 1916.

-

@Kehaulani said in Company Timelines (Besson, Diston-Keefer, Frank Holton, Vincent Bach):

Fascinating. Could you tell me why the pre-WWII French Bessons were legendary, how Benge and Schilke came into this mix, and what modern trumpet would be the closest to the Besson? Thanks.

This question is purely an opinion. Some may feel that the pre-war F.Bessons are nothing special, others connect with a mystique that dates back a century.

Around 1880, the Besson trumpet we think of as a Brevete, was the first valved trumpet that was practical. Prior to that time, and for most makers well after, “trumpets” came in a variety of keys, could be pitched with crooks like the inventionshorns they were, and had bores often made up of cornet parts. The Besson design captured the sound and feel of a natural trumpet – probably by being a compact (and half-wave) version thereof with the addition of a valve block. Until 1911, if you came into a serious orchestra, chances were that the conductor would not tolerate the sound of cornets and these half-breed trumpets. They would only tolerate the pure trumpet tone of natural trumpets, baroque slide trumpets (played at an angle with a 1.5 step slide on a plunger that pushed back past the face, not soprano sackbuts), vented natural trumpets like Haydn wrote for, or Besson chromatic trumpets.

Which would you choose to play?

Then in 1911 the Holton company introduced their New Holton Trumpet. By today’s standards the tone was thin, bright, and a bit harsh. But it was a trumpet tone. With the right mouthpiece, it could be a clear, crystal penetrating and semi-strident sound in keeping with that of a natural trumpet. By 1920, Holton moved on to the Revelation concept which proved more suited to swing clubs than concert halls, but Conn picked up with the 2B and the amazing 22B. This and the rise of Courtois, Couesnon, and ultimately Selmer in 1932 in France really bit into the market for Fontaine-Besson. Besson production tapered off from WWI to WWII as sales tapered even further (this is why we have the overlap of old and new designs in the serial numbers in the 90-99,000 range as parts and whole horns were stashed for later sale).

For American orchestral trumpeters, the scarcity that resulted from contraction at Besson in the 1930s – and which brought about the sale of the firm to SML – left serious players with aging instruments and no new ones in the market that had the pretentiousness of a “French Besson”.

That will bring us to question #2

Elden Benge was originally a cornetist, as his father had been a minor celebrity cornetist. He famously wrote a letter to HL Clarke asking about switching to trumpet to adapt to societal change which in his response to, the noted virtuoso equated “Jaz” with the closest thing to Hell and the Devil. Benge studied with Edward Llewellyn, principle trumpet in the Chicago Symphony, and ultimately succeeded him when Llewellyn’s teeth failed. Llewellyn was still acting as an orchestra manager and road man for Holton when, a few miles from an 8 year old Byron Autrey’s home in Texas in the early 30s, he slept in the passenger seat as his wife drove toward an oncoming truck with pipes on a rack overhead. The truck drifted into their lane and Mrs. Llewelyn attempted to pass on the wrong side. But as the truck drifted off the road, the driver awoke, overcorrected, and the two cars met in an offset frontal impact which sent pipes flying forward decapitating Llewellyn (story courtesy of Byron a few weeks before he passed).

At the same time as he became one of the world’s most visible trumpeters, Benge found himself with a Besson that was wearing out. Benge had a friend, nieghbor and fellow CSO trumpeter named Renold Schilke. Schilke had apprenticed at Holton in the mid 1920s and in 1927 studied advanced instrumental acoustics for a year in Belgium. Upon his return, he collaborated with his teacher on the Llewellyn model Holton, concepts from which he would apply in 1937 to the design of the Committee for Martin. Benge asked Schilke for help, and Schilke taught him the fundamentals of brass making in a garage workshop. Benge then dismantled his favorite Besson and used it as a template for making parts to repair others.

Before too long, Benge, probably with input from Schilke, Llewellyn, Holton designers and others, was making “improvements” to the basic Besson bell tapers and working/annealing cookbook (the “Resno-tempered” concept). It motivated his transition from modifying/resurrecting old semi-sacred at the time Bessons, to making better Bessons.

After serving in the Navy in WWII, Byron Autrey, who evidenced a natural feel for the scientific basis of tone production that Schilke preached as gospel, came to work with Benge as his first road man and technical collaborator. Perhaps Byron’s talent for bell tapers was learned from Benge and Schilke, but it was Byron who was the master of leadpipe design in perfected pairing with the bell taper (a personal passion of Schilke’s). Byron took Schilke’s ideas and was able, largely by innate feel, with some numbers thrown in for psychological comfort, to adapt them to tweaking Besson leadpipe tapers to achieve the ever moving target Benge had of a “Better Besson”.

When Benge died in 1960, it appeared that ongoing evolution would end, but Byron lived on, and took as his inheritance that passion for a better Besson (among other makes such as Bach, Reynolds, Martin, Edwards, Kanstul, …).

That brings us to question #3.

Irving Bush had been another collaborator with Elden Benge. When Benge died, he stepped in and took over QC for the company and was instrumental in its survival. He was the one who preserved the pieces found in Benge’s workshop from that first Besson so that Lou Duda, master maker and father of John Duda who carries on the Calicchio tradition toady, could reassemble it. Bush, of course, interacted with Schilke and Autrey as time went on, but the company itself was doomed by the market forces that consolidated almost all the great makers out of existence. As it spiraled out, Zig Kanstul, an apprentice of Foster Reynolds (an apprentice of assorted long lines of masters), Harper Reynolds, and Benge himself, briefly tried to salvage that heritage directly before bailing out and ultimately partnering with Elden’s son and heir Donald Benge (the same one famous for board games) to produce Benge/Besson heritage horns in 1980.

That venture inspired Kanstul to buy the former Benge plant with all the tooling still sitting there, and not only stencil those horns for “Burbank”, but sell them under the Kanstul name and ultimately make perfectly faithful Besson Brevete and MEHA replicas under contract to the owners of the Besson (ironically English Besson not French) name. Byron Autrey joined the effort, as was his style quietly but dominatingly, behind the scenes. Zig Kanstul relied on both the extensive research he and R. Dale Olsen had done together at Olds with vintage Besson bells and leadpipes as part of the “Olds Custom” project, and on Byron’s improved interpretations in the spirit of their mutual friend Benge. Byron adjusted the bell for one model, and the leadpipes for all, making them embody, yet improve on as Schilke always sought, the performance of the Besson originals they sounded exactly like.

When the end came at Kanstul in 2019, the Benge/Besson heritage was still strong. Just before Mark Kanstul threw in the towel, the firm had moved forward plans to once again reintroduce these models to a market still hungry for them. In the ensuing chaos, priceless assets like the Benge annealing ovens went for scrap prices on EBay. Eventually, the upstart BAC Musical Instruments, with its charismatic front man and founder backed by the business acumen and finances of the leadership of “Rent my Instrument” with which the firm had previously merged, and supported by the advice of John Duda, stepped in and bought what was left after those EBay sales and some transfers to a long time Kanstul employee.

To augment and complete the hodge-podge of tooling, documents, models and parts, BAC was put in contact with the estate of Byron Autrey. From that channel, they secured priceless tools, experiments, personally optimized Benge horns and other resources. The final crowning element came when they successfully secured rights to the Benge trademark.

The BAC Benge is a Benge, which is a Besson. It is the culmination of 140 years of developing the French Besson concept of trumpet sound – the original chromatic orchestral trumpet sound. The “Chicago” leadpipe option is a faithful recreation of an optimized Besson pipe in the Benge tradition. The “Burbank” pipe, is the final ultimate achievement of all of these masters working over nearly a century and a half up until shortly before Byron’s sudden death just last year. It is faithful to the French Besson concept, but improves upon the consistency, intonation, and flexibility far beyond what the originals offered a player. Of course, the more any technology can do for you, the more it can do to you, so the choice between Chicago and Burbank is one between more and less stable – or more and less constraining – depending on your desires/abilities as a player.

Obviously, I feel, based on the history and upon the testimony of those who have played them, that the answer to your third and I suspect primary question is the Benge Trumpet from BAC.

-

That was fascinating, thanks.

Just a quickie - I thought BAC was still in transition and not selling their Benges yet. -

@Kehaulani said in Company Timelines (Besson, Diston-Keefer, Frank Holton, Vincent Bach):

That was fascinating, thanks.

Just a quickie - I thought BAC was still in transition and not selling their Benges yet.It appears you are correct. Retail availability now looks like this fall - Covid seems to have interrupted tooling efforts for a while. I am told they still have to get the production valve making tooling set up, and then should be ready.

The other new BAC trumpets are out now if you happen to be interested in one of those (your local dealer is Strait Music - in front of Target at the base of the freeway triangle off S. Lamar - looks like they only stock Yamaha, B&S and Bach in inventory. Maybe you can persuade them to show Benge as well?)

-

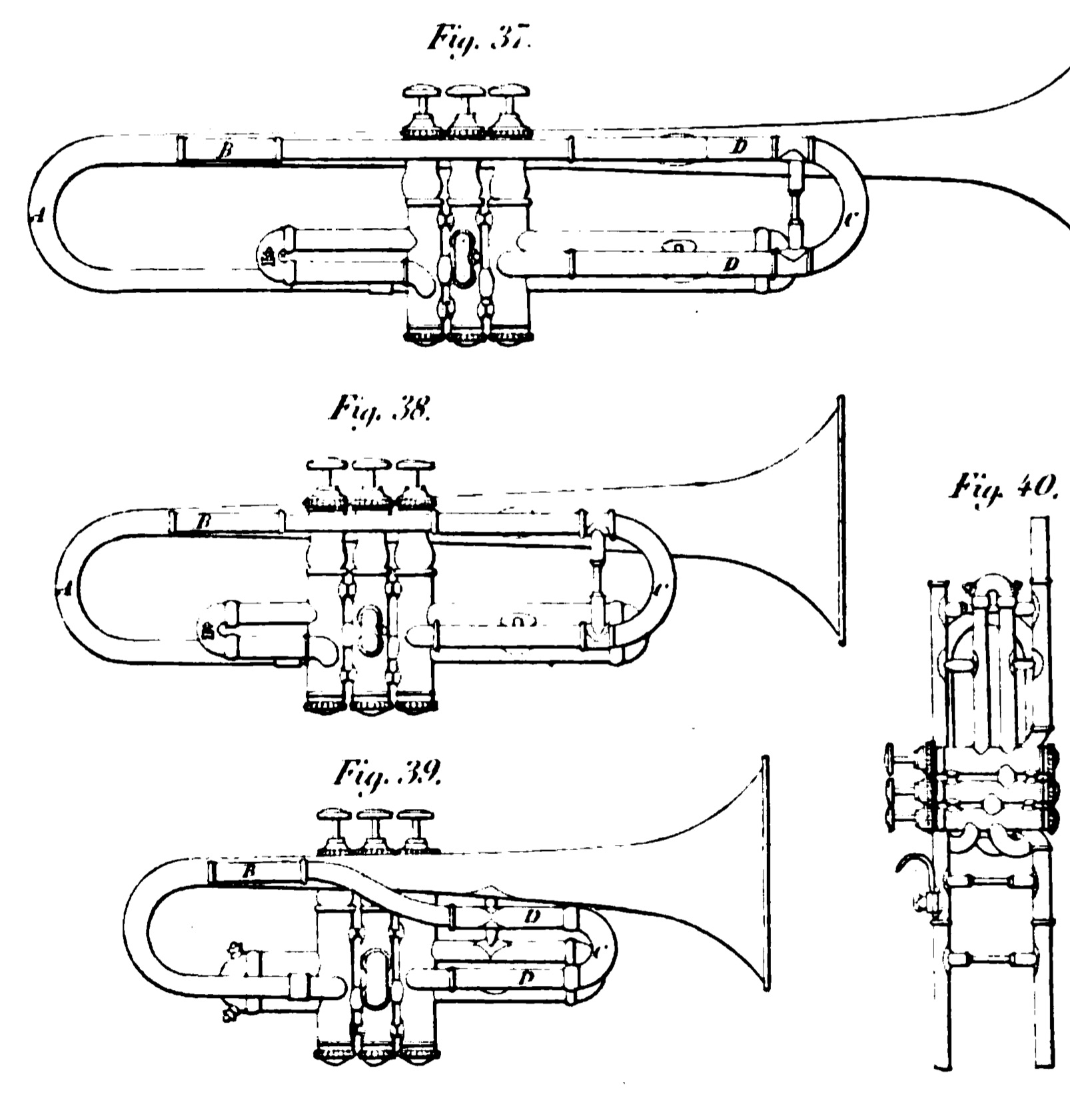

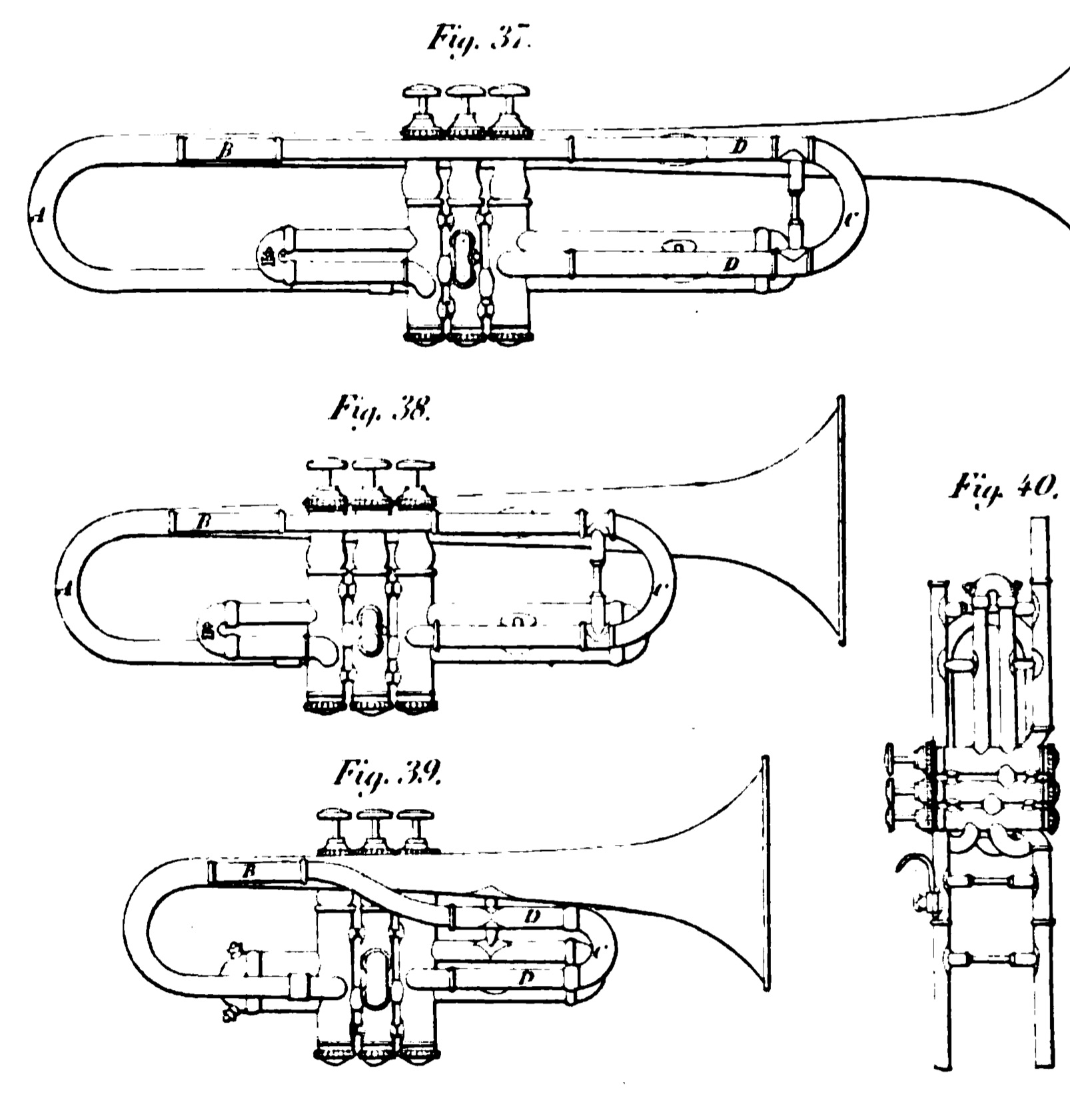

One small addition to the Besson timeline, The Besson "Breveté" (patent) for the modern trumpet is from 1867. Here is an illustration from that patent .. it looks like a modern trumpet, eh?

The top one is in A I think and the middle one is in C.

The top one is in A I think and the middle one is in C.

I am sure there were some examples made in this period but they don't appear to have survived or are still in an attic somewhere.

-

@OldSchool, I may have asked you before (age befuddlement), but is there a modern trumpet that is the same as a pre-WWII French Besson? And, now that a lot of time has passed, in comparison with modern horns (any brand), what are the advantages and disadvantages of the Besson? (if it exists)?

-

@Kehaulani said in Company Timelines (Besson, Diston-Keefer, Frank Holton, Vincent Bach):

@OldSchool, I may have asked you before (age befuddlement), but is there a modern trumpet that is the same as a pre-WWII French Besson? And, now that a lot of time has passed, in comparison with modern horns (any brand), what are the advantages and disadvantages of the Besson? (if it exists)?

I apologize for butting in, but would like to make some points.

To make a trumpet "the same as a pre-WW11 French Besson" you would have to recreate the types of machinery used, the exact preparation of the brass alloy used, the exact methods used e.g. bending with lead. Even if you did duplicate the design right down to the valve geometry and port wall thickness etc.

Some major idiosyncrasies of the French Besson trumpet are:

angle of 2nd valve slide

valve casing elbows are "outside tubes" not "inside (bore diameter) tubes

relatively thin gaugePlus some other details like the top valve cap is 2 pieces soldered together rather than 1 piece. All this makes a difference (better or worse - the player's choice).

Incidentally when Vincent Bach said that his trumpet was based on the French Besson, his trumpet had none of these features.

-

@Trumpetsplus said in Company Timelines (Besson, Diston-Keefer, Frank Holton, Vincent Bach):

@Kehaulani said in Company Timelines (Besson, Diston-Keefer, Frank Holton, Vincent Bach):

...the exact preparation of the brass alloy used, the exact methods used e.g. bending with lead. Even if you did duplicate.AND that would be impossible with Federal restrictions place on lead content in brass that was in effect post 1952.

-

Good new here is I was born in 1955, so I am lead free!

-

@Dr-GO said in Company Timelines (Besson, Diston-Keefer, Frank Holton, Vincent Bach):

Good new here is I was born in 1955, so I am lead free!

That may have just made room for other contaminants!

-

Thanks for the replies. I should've been more specific. I'm not concerned about the metallurgical properties or other such parameters, as much as I am concerned with how it plays and sounds. In other words, I don't so much care how one got there but what the results are.

-

You guys all got ahead of me on this one.

There is no way to build a perfect pre-war Besson. The tooling and the tech were lost in the Couesnon arson if not before. Byron theorized that their annealing techniques may have been quite unique. We will never know.

In terms of play & feel, I can only say that I have a late pre-war Brevete, and that I have put it side by side with the Kanstul version, and the sound & feel were a match in my judgement and that of others. The tricky thing is, just because 2 horns matched, does not make an equation. We are talking about a period of hand work where variability was a constant if you will excuse the humor. On average, I think Kanstul had it nailed, but in terms of matching specific iterations, its not really possible.

That patent is for the designs that precede the classic Besson wrap by the way. Like so many others of the day, it is lacking in many respects relative to the definition of the modern trumpet Besson would establish not long after.

-

Sorry, I overlooked the second part of the questions.

My personal opinion is that the only advantage in the real thing, or a precise match for the average of the real thing, would be historical authenticity.

Benge improved on forming and tempering of bells still in that French profile, adding color and depth to the sound.

Schilke improved on the native intonation with his input to Benge and arguably his own B series - though they are not horns I consider in the same French style.

Autrey built on the work of those two refining the leadpipe tapers and at times even the bell to further optimize the overall bore progression and thus both intonation and tonal complexity/flexibility.

Give me a modern horn please! (at least if I'm going to be heard playing it)

-

@scottfsmith said in Company Timelines (Besson, Diston-Keefer, Frank Holton, Vincent Bach):

One small addition to the Besson timeline, The Besson "Breveté" (patent) for the modern trumpet is from 1867. Here is an illustration from that patent .. it looks like a modern trumpet, eh?

The top one is in A I think and the middle one is in C.

The top one is in A I think and the middle one is in C.

I am sure there were some examples made in this period but they don't appear to have survived or are still in an attic somewhere.

I’d guess the bottom one is in Eb, since that was a predominant key for brass instruments at that time, and the shape is similar to some Eb cornets.

-

@OldSchoolEuph said in Company Timelines (Besson, Diston-Keefer, Frank Holton, Vincent Bach):

That patent is for the designs that precede the classic Besson wrap by the way. Like so many others of the day, it is lacking in many respects relative to the definition of the modern trumpet Besson would establish not long after.

It looks pretty similar to me in terms of the tubing, the main difference I see is how the 2nd valve slide comes right out. There are a few existing early Besson trumpets in fact that have that sticking-out side. What looks so different to you? It is an illustration so the proportions are not perfect, for example the valve casing decorations are too curved.

-

@OldSchoolEuph A quick vote of thanks to OldSchoolEuph for posting this info and to all those members who have offer informed thoughts and commentary.

It's this type of posting that drew me TH and the late lamented TM in the first instance. I would not deny that there is room for this type of information and social intercourse, however I would suggest that the more learned material that is posted, the greater the possibility for the site to attract a wider membership base.Just my thoughts, there I've said it.

Regards Tom

-

Locked by

barliman2001

barliman2001